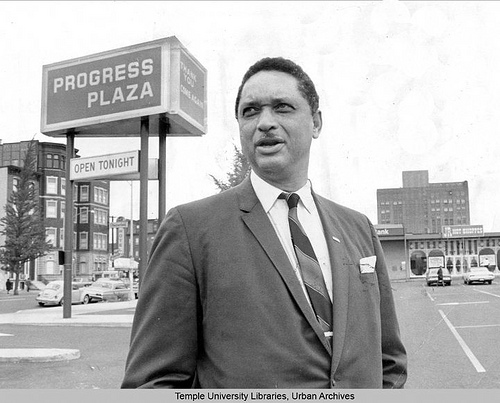

Our Founder

Reverend Dr. Leon Sullivan

This 6-foot-4 giant of a man had a voice that resonated so much that he was often referred to as the “Lion from Zion.” In his book “Build Brother Build,” Leon Howard Sullivan speaks of growing up poor in Charleston, W.Va., and being raised by his grandmother. His first personal experience with racism was being denied the right to sit down to order a soda in a local store. He decided then to work toward equality and remained committed to that goal his entire life

He attended West Virginia State College on a basketball scholarship. Always active, he was impressed by a speech at an NAACP event given by Adam Clayton Powell; Powell then invited Sullivan, who was studying at Union Theological Seminary at the time, to become assistant pastor at Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem. Sullivan was also mentored by the great union organizer A. Phillip Randolph, who had the vision for the first March on Washington in 1941 to eliminate job discrimination in Army and Navy industrial installations. (The march was called off a few days before its scheduled start because President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, which outlawed such discrimination.)

Sullivan came to Philadelphia in 1950 to pastor Zion Baptist Church and started working to find jobs for youth and get them off the street corners. He helped establish the Citizens Committee Against Juvenile Delinquency, which created a massive organization of community volunteers that worked to not only help prevent juvenile delinquency, but also tackled problems of housing, employment and other issues confronting the Black community.

In 1960, Sullivan organized 400 African American ministers and they initiated the “selective patronage” campaign (it was illegal to restrict trade). Tastykake was the first company to which the ministers presented “reasonable demands.” The company resisted for a while but finally gave in to the demands because they were losing money. Twenty-nine companies hired or promoted Black Philadelphians between 1960 and 1963, resulting in some 2,000 skilled jobs.

As more and more African Americans obtained jobs, companies began to complain that they were not skilled enough for some of the positions. Thus, Sullivan saw the need for job training, and Opportunities Industrialization Centers (OIC) was born. The first OIC opened in an old abandoned jailhouse at 19th & Oxford Streets with thousands of people witnessing this new venture.

As he continued on his crusade of “racial economic emancipation,” Sullivan implemented the “10-36 Plan.” He asked 50 members of his congregation to donate $10 per month for 36 months to an unrestricted cooperative program. Two hundred members responded the following Sunday and in a couple of years, there were 400 more members. In 1964, they purchased a $75,000 apartment building under the aegis of Zion Investment Associates, which became Progress Investment Associates (PIA). In 1965, they broke ground for Zion Gardens, a million dollar garden apartment complex, which, at the time, was the first of its kind and size in Philadelphia history to be developed and owned by African Americans.

In 1967, the group broke ground for a $2 million shopping center with a 20-year, million-dollar lease with the A&P food store chain — which marked A&P’s largest agreement ever made with a Black company in the history of America. The deal also mandated that all chain establishments have black management.

Continuing on the road to economic emancipation, PIA established the Entrepreneurial Training Center, National Economic Development Center, Progress Aerospace Enterprises, Progress Garment Manufacturing Enterprises & Ten Thirty-Six Fashions and Progress Stores. The “10-36 Plan” eventually grew to include more than 3,000 shareholders.

The Rev. Dr. Leon H. Sullivan’s legacy is manifested by the hundreds of thousands that have attended and graduated from OICs throughout the world; the businesses owned by Progress Investment Associates; the renovated Sullivan Progress Plaza; and the thousands that have benefited from programs he initiated. Sullivan paved the way for today’s most influential African Americans in Philadelphia.